Finding Your Roots

Hard Times

Season 5 Episode 8 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

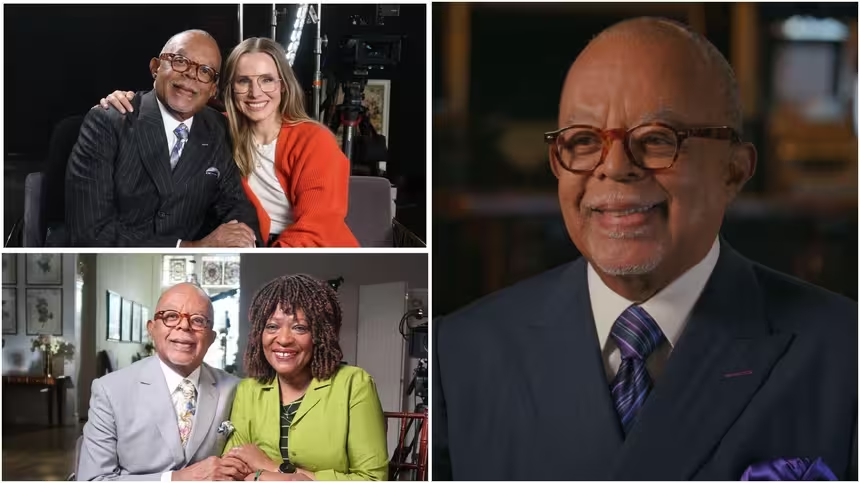

Dr. Gates explores the stories of Laura Linney, Michael Moore and Chloë Sevigny.

Host Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the family stories of filmmaker Michael Moore and actors Laura Linney and Chloë Sevigny—three people whose distant ancestors overcame great hardships in ways that resonate with their lives today.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Hard Times

Season 5 Episode 8 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Host Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the family stories of filmmaker Michael Moore and actors Laura Linney and Chloë Sevigny—three people whose distant ancestors overcame great hardships in ways that resonate with their lives today.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGates: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots".

In this episode, we'll trace the family trees of filmmaker Michael Moore, and actors Laura Linney, and Chloe Sevigny.

Three people whose ancestors overcame formidable hardships to lay the groundwork for their success.

Sevigny: Poor Marguerite.

From child to bride.

Poor girl, it must have been terrifying.

Linney: What's most surprising is this pattern of all these women who've been heartbroken.

And who have had a heavy load to bear.

Moore: I'm so afraid to turn the page.

Just tell me he's gonna be okay.

Gates: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists helped stitch together the past from the paper trail their ancestors left behind.

Linney: Wow!

That's amazing.

Gates: While DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

Sevigny: No!

Gates: Yes.

Absolutely.

Sevigny: Really?

Gates: And we've compiled it all... Moore: Wow.

Gates: Into a book of life.

Linney: I knew you all existed, I just didn't know who you were.

Gates: A record of all our discoveries.

Moore: You know when people say that something has touched them deep in their soul.

That is what has just happened in this moment.

And um... Wow.

Gates: Michael, Laura, and Chloe share a common thread: each descends from women and men who faced daunting challenges.

In this episode, they'll discover how their ancestors met those challenges, hearing stories of sacrifice, courage, and survival, all hidden in the branches of their family trees.

(Theme music plays) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Moore: Here's the power!

Here's the majority of America right here!

Gates: Michael Moore is a progressive firebrand blessed with a mischievous sense of humor.

Moore: Boy, here's my first question, do you think it's a little dangerous hanging up guns in a bank?

Gates: For more than 30 years, he's been making documentary films that are politically conscious, artistically innovative, and remarkably entertaining.

Moore: We're here to get the money back for the American people.

Security: I understand sir, but you can't come in here.

Moore: Can you just take the bag?

Take it up there?

Security: No.

Absolutely not.

Moore: Hey, just drop it from the windows.

Gates: His work is controversial, but no one can question his passion or his commitment to his beliefs.

Characteristics he's displayed since he was a child.

When he was a boy, Michael even wanted to become a priest, because he admired the liberal wing of the Catholic Church.

Moore: There was always this sort of radical left part of the church, and I wanted to be part of that, and I wanted to leave at 14 to go to the seminary, and my parents didn't want me to leave home, but all you have to say to an Irish Catholic parent is that you have a calling.

Gates: That's it?

Moore: And you don't want to get in the way of that.

So, they let me go, and so I went for 9th grade, and uh sometime during that year, between the age of 14 and 15, the hormones kicked in and I read the rulebook, and... Gates: And that was that?

Moore: I realized, yeah, this wasn't gonna work out.

And so I went in to tell the priest that I was leaving the seminary, and he said, "Oh, that's funny because we were gonna tell you not to come back."

Gates: Really?

Moore: Yeah, I was like, no, you can't fire me, I came in here to quit.

Gates: Yeah, right, I quit.

Moore: I said why would you want me to not come back?

He goes, "Because you ask too many questions."

Gates: The priest was probably right.

Michael seems like he's been asking questions since he first learned to talk.

In no small part, because he's had an awful lot to ask questions about.

He grew up in Flint, Michigan, an auto town, watching his father work on an assembly line and realizing that something was amiss.

Moore: I appreciated the fact that my dad, you know, made spark plugs at General Motors to put in those cars, and the sacrifice of that work, for us, uh, but also part of that working class ethos is the understanding that, don't be fooled by the lies that are told... Gates: Right.

Moore: by those who have the money.

Gates: Uh-huh.

Moore: And those things stayed with me, I guess.

Gates: Michael launched his career by skewering his father's employer in his first documentary, 'Roger & Me'.

Michael: What do you think about General Motors closing up this factory?

Woman: This is a very private, emotional family time and we would not let any outsiders in the plant.

Michael: We're not outsiders, we're all from Flint.

Woman: You are an outsider, you don't work here.

This gentlemen is working right now.

Michael: Well, this community depends on General Motors.

Woman: Jerry...this guy...out!

Gates: The film is remarkable not only for it's critique of corporate capitalism, but also because it's so deeply attuned to the lives of the workers who struggle within the system.

A perspective that Michael says flows out of his father.

Moore: I remember me and my dad, we were driving around Flint, one day, and I was, you know, an adult at this point, and he said, "Turn down this street."

And went down to the, it was a dead-end street, and he said, "This building here is where I spent 4th and 5th grade."

Uh, I said, "What, you mean like was it a school?"

He said, "No, it was an orphanage."

I said: "Why were you in an orphanage?

Your parents were both alive."

He says because they couldn't afford seven kids and uh, I kept thinking: "You've been through this, how are you still this sort of, uh, basically saintly person?"

Gates: Yeah.

Who loves his children.

Michael: Yeah, but, that's who he was and that's, that's ugh, that's the gift that he was to us kids.

Linney: There goes a man, who has open the door to our future!

Gates: Like Michael, renowned actor Laura Linney is very much a byproduct of her childhood.

Laura was raised in New York City, the Mecca of American theater, and her father, Romulus Linney, was a well-known playwright.

On the surface, her career seems preordained.

But the reality is much more complicated.

Gates: I'm sure that people said that your theatrical inclinations, it's in your DNA, it comes from your daddy.

Linney: Yes.

Yes.

Gates: Girl's just like her daddy.

Linney: Yes.

Yes.

Gates: And you go, "I am like my daddy."

Linney: Yes.

But, he was not always the happiest guy so there were times where it was... Gates: He's a playwright.

Linney: He's a playwright.

Gates: There are no happy playwrights.

Linney: No happy playwrights.

There are a few but not many.

Gates: Few, yeah.

Linney: Um, you know, and he didn't have the easiest time, and he didn't quite know what to do with a child.

Gates: While Romulus may have given his daughter a genetic inclination towards the stage, he didn't play an active role in guiding her there.

He and Laura's mother Ann divorced when Laura was an infant, leaving Ann a single parent, and forcing Laura to drive her acting ambitions forward on her own.

Did you do skits for your mom, for your family?

I mean, did you... Linney: Oh, sure.

Oh, obnoxiously so.

Absolutely.

Oh, yes.

I was one of those obnoxious, you know, theater brats.

Um...and I was, you know, obsessed with everything that, that came to Broadway, and actually I had a very hard time learning how to read and write.

And so I would sort of swing deals with my teachers, you know, about...and it was the seventies so they were a little open to it.

Gates: Yeah, right.

Linney: About, you know, let me act it out, or let me, you know, do something creative.

Let me make a collage about that book as opposed to actually writing a book report.

Gates: That's pretty clever.

Linney: It was clever.

Gates: And it worked.

Linney: It worked.

It wasn't necessarily the greatest choice in the long run, but it was, it was good at the time.

Gates: Laura is being modest.

Her choices have worked out quite well in the long run.

She's had incredible success, on both stage and screen, for decades, working at a breakneck pace, in an industry famed for discarding its own.

Her secret?

According to Laura, her upbringing left her well-equipped to deal with whatever show business could throw at her.

Linney: My family is modest.

You know, expectations are, um, realistic, and that's helped me tremendously.

Gates: Expectations are realistic?

You're a little girl on the east side and you go, "I'm going to go to Broadway."

Linney: I know.

I know.

Gates: That's a fantasy.

Linney: I know.

Absolutely.

Gates: I mean, you shot for the moon.

Linney: That sort of wasn't on my mind.

I wasn't the kid who thought I'm gonna be on Broadway or I'm going to be in the movies.

I just thought I really like being in this class.

Gates: Oh.

Right.

Linney: I really like, I want to go to that school.

Gates: That's a blessing.

Linney: Very much so.

Gates: It is.

Linney: I have a, I have a very good disposition for this business, and I realize in some ways that's the greatest gift I have.

Gates: My third guest is actor Chloe Sevigny.

Chloe's won stardom through her daring, unconventional, and challenging roles.

From "Kids" and "Boys Don't Cry" to "Big Love" and "American Horror Story".

It's difficult to think of another actor who has portrayed so many different kinds of characters, all with such a fiercely independent spirit.

Sevigny: Why can't you leave us alone?

Gates: It's a quality that, according to Chloe, comes from her father, David Sevigny.

Raising his family in Darien, Connecticut, an affluent suburb of New York City, David encouraged his children to be themselves above all else.

Sevigny: I think my father was very bold and I think that I've inherited that from him and he was very self-assured in who he was and really encouraged my brother and I to be individuals.

We grew up in a very, you know, small community and he, you know, always encouraged us to do our own thing and, you know, not follow the rest of the kids.

Gates: That's good.

Sevigny: And to be individuals and I think he really instilled a strong sense of that in us.

Gates: Her father's advice would have far-reaching consequences.

By the time she was in high school, Chloe was doing her own thing in almost every regard.

Taking long road trips to Vermont, hanging around Greenwich Village, and ultimately deciding to forgo college.

Sevigny: I was really uh into music and art and fashion.

Not into academics, not into the kids that I'd grown up with my whole life.

I think I was just very curious and felt really stifled in in, in the town that I grew up in and and was like searching for something else.

And I was just like a little sponge.

I'd go into Washington Square Park and just stare at everybody and everybody was always like: "Chloe has a real staring problem."

Gates: Did your parents give you grief about not going to college?

Sevigny: They were pretty cool with it.

I mean my brother was going to college.

He was kind of on the right track and he had been kind of more of the troubled one so he had turned it around and then by the time I came up there I think they were just kind of like oh, whatever.

Gates: Chloe's decision was quickly justified by her success, she transformed from a "sponge" to a celebrity almost overnight.

And though she's moved on from her suburban home town, Chloe's never lost touch with her roots, remaining bonded to her parents, and confirming, profoundly, their faith in her.

Gates: Your father always told your mother, I read, quote, "That there's more good in the world than bad.

Chloe's going to be okay."

Sevigny: That's true.

When I'd drive off in my Volkswagen bus up to Vermont sleeping on the side of the road she'd be like what are we doing with our daughter?

And he would say that.

There's more good in the world than bad.

Gates: Do you think that all the stability... Let's call it the white bread stability you had in Darien actually freed you to be the voyeur into Washington Square Park.

You know, you always had a safe place to go back to?

Sevigny: Yeah.

Gates: So that freed you, to identify with these alternative kinds of characters.

Sevigny: I think so.

I mean people think, often refer to me as doing all this risqué work and always being in controversial films and really I'm like a nice girl from Connecticut.

And I think having that stability and um relationship with my family and that, you know, stronghold, that safety has has freed me up in my artistic endeavors, you know.

Gates: Yeah.

To experiment and be risky.

Sevigny: To wild out.

Yeah.

Gates: Yeah to wild out.

I like that.

Meeting with my guests, I was struck that each was so self-determined, so proudly willing to pursue their own path, regardless of the consequences.

I wondered if their family trees would be filled with like-minded people.

Michael: We've been told that we're 100% Irish.

Gates: I started with Michael Moore, and I didn't have to look far to find out.

Michael's father Frank served in the Marines during World War II, endured some of the worst fighting imaginable, then emerged as a pacifist.

Moore: He was in every one of those awful battles in the South Pacific where if you've seen "Saving Private Ryan" that first half hour where they land at Normandy... Gates: They just go (bullet sound).

Moore: Yeah, the door comes down on the amphibious vehicle.

Gates: Yeah.

Moore: And half of them are dead.

Gates: Yeah.

Moore: And, and that's island after island after island that he did that, and I don't know how he survived, I don't know how he, uh, maintained himself as the father that we knew, as a kind and gentle soul, uh, but he was very much opposed to war in the sense that he would always say that uh anybody who's been to war would never want to send anybody else to war.

If you've really been in war, it's the last thing you want to do, it's the last absolute last alternative.

Gates: Michael told me that his father's pacifism had profoundly shaped his own worldview.

Incredibly, as we dug into his roots, we discovered that Frank wasn't the first in his family to oppose war.

Not by a long shot.

Moving back on his paternal line, we came to Susannah and Henry Hoover, they are Michael's third great grandparents.

We found them, in Indiana in 1810, listed in the minutes of a group known as the "Whitewater Friends."

And Michael was immediately struck by the word "friends".

Moore: Is that friends as in, as in religious?

Gates: Friends, yes.

Moore: You mean like friends like Quakers?

Gates: Like Quakers.

Moore: Wow.

Okay.

Gates: Yeah.

Moore: Wow.

That is amazing, and such a good feeling, too, because, you know, as we know, Quakers are uh, are pacifists, are people who believe in peace, and if you've ever been to a Quaker meeting or have friends who are Quakers, uh, amongst the kindest, most loving people you'll meet.

Gates: And you had no inkling that you had Quaker heritage or anything in common with them?

Moore: Oh, no, no.

We're Catholic, and the few Irish in our family that are Protestant, we just assumed somebody took the soup, as they, as they would say.

You know I think if my parents were alive and heard this, they would be in shock, not bad shock, just there's nothing, uh, in our upbringing where any of this was ever shared.

Gates: Michael's father would have been particularly shocked by what we discovered next.

In 1812, America went to war with England.

Michael's ancestor, Henry Hoover, was called to serve in a militia.

But, driven by his faith, he refused to take up arms.

An experience that he later described in a memoir.

Moore: "Being then a member of the society, a compliance would have ejected me from the church and moreover brought trouble, on the minds of my parents, who had taught me that all wars were anti-Christian and contrary to the doctrines of Jesus Christ."

Gates: You just read the writings of your third great-grandfather.

Moore: Oh my God.

I am so deeply moved by this.

Wow.

You know when people say that something has touched them deep in their soul?

That is what has just happened in this moment, and uhm, wow!

Gates: According to his memoir, Henry Hoover was court-martialed and fined for his disobedience.

But an even greater challenge lay ahead.

In 1827, the Quaker faith was thrown into a crisis by a minister named Elias Hicks, a radical reformer who challenged an array of orthodox beliefs.

Hicks inspired a schism, which shattered Quaker communities throughout America.

We wondered how Henry responded to the reformer's call, and found the answer in the minutes of his meeting.

Moore: "August 26, 1829, Henry, d-i-s for j-a-s."

Gates: Want to guess what those initials stand for?

Moore: Uh, "d-i-s" for "j-a-s"?

Gates: Uh-huh.

Moore: Uh, no, I feel like I'm on "Wheel of Fortune" now and I need one more vowel.

"Dis" for "jas"... I have no idea what these mean, but the tone of it is... Gates: Bad news.

Moore: That he has been booted.

Gates: That's right.

Moore: He has been booted from the Quaker meeting for, for what?

Gates: Because he joined the Hicksites.

Henry Hoover "disowned for joining another society."

Moore: Wow.

Gates: Disowned.

Moore: Disowned.

Gates: For joining another society.

Moore: Another society.

Gates: Yep.

Moore: Wow.

Gates: Henry was expelled from this meeting as a part of the schism.

Moore: Unbelievable.

Good for him.

This is two very brave acts.

Gates: Big time.

Moore: Wow.

Oh, man.

Does life get any better for him?

I guess I'm so afraid to turn the page.

That this guy, that they have not done away with him yet.

Just tell me he's gonna be okay.

Gates: Henry would, in fact, turn out to be okay.

After his expulsion, he ultimately found his way to the Methodist church, and lived to be almost 80 years old.

But the Hicks schism clearly scarred him, and brought his family decades of grief.

Moore: "23 years have passed away since this Quaker separation, yet the unkindness and malign feeling still exists."

Wow.

Do you think he's referring to the unkindness brought upon him?

Gates: Yes, being kicked out of the... Moore: And being maligned.

Gates: Yes, being kicked out of the meeting.

Moore: Wow.

Gates: That he was treated in an unkind way.

Moore: And then it reads on, it says here, his parents joined him in following Hicks, and they, too, were...were disowned.

Gates: You can still feel the pain.

Moore: Yeah.

Gates: These are my friends and neighbors.

They turned against me.

They kicked me out, and I'm still hurt.

Moore: Wow.

Gates: That's a remarkable thing to admit.

Moore: Man, I which I could reach back into time and give him a big hug.

Gates: My next guest, Laura Linney, has deep roots in the American south.

Her mother, Ann Legett, was born in Nicholls, Georgia, a tiny town where much of her family lived for generations.

It's a place that resonates with sadness for Laura.

Ann's father died when she was a child, leaving her mother with four young children, struggling to support herself.

How did your mom tell you about this?

What did your mother say?

Linney: Well, there was a sense that they were, you know, abandoned, and that there was great fear, and that there was not security, and that there were thankfully people from, I don't remember if it was the Rotary Club or the Lion's Club or one of those community clubs that would, would help them financially occasionally, and that my grandmother opened a laundry in the back of the house in order to pay for things.

I don't think they ever fully recovered quite frankly.

Gates: Your mother told us that the family was, quote "plunged from heaven to the ring of hell."

Linney: Oh.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah.

That death is still around.

Gates: As it turns out, Laura's grandmother wasn't the first woman in her family to find herself in dire straits.

Moving back one generation, we came to another: Laura's great-grandmother, a woman named Ruth Leggett.

We found her living on her own, far from the family seat in Georgia.

This is a page of the 1930 federal census, for a town called Eustis, Florida.

Linney: Florida?

Gates: Yup.

Would you please read the first transcription?

Linney: "S. Ruth Leggett."

Gates: Mm-hmm.

Linney: "Head.

Marital condition, W."

Gates: You know what W... Linney: Widowed.

Gates: Widow.

That's right.

So, your great- grandmother, Ruth, that's listed as a 45-year-old widow living with her three children... And so we wanted to find out more about Ruth's husband, Milton Sr., who would have been 47 years old at the time.

Any family stories about how he passed away?

Linney: No.

I don't know much about them at all.

Gates: We set out to see what happened to Milton, and ran headlong into a mystery.

His death certificate is dated June 21, 1962.

That's more than 30 years after his wife Ruth reported herself as a widow in the 1930 census!

So, was the death certificate wrong?

Or was Ruth lying to the census taker?

The answer would reveal why Milton wasn't much-discussed in Laura's family.

Laura, this is the census for Raleigh, North Carolina... Linney: Raleigh.

Gates: From 1930, the same year that your great-grandmother Ruth was listed as a widow.

Would you please read the transcription?

Linney: "Milton M. Leggett, roomer.

Marital condition, single."

Wow!

Gates: Well, Milton was alive and well when... Linney: In Raleigh.

Kickin' up his heels in Raleigh.

Gates: In Raleigh.

And meanwhile his wife is claiming to be a widow.

Do you have any idea why Ruth would have told the census takers she was a widow, Milton was actually still living?

Linney: She was embarrassed by him.

It had to have been that.

Gates: Yeah.

I would think so, right?

Linney: She was embarrassed by him.

Gates: Divorce in the south in the 1930s would have been a stigma.

Linney: Yeah.

Wow.

Gates: Now what do you think that must have been like for Ruth pretending to be a widow, knowing full well that your husband was alive and well and living another life?

Linney: Well, that's why she moved to Florida.

Gates: Mm.

Right.

To escape detection.

Linney: Yeah.

Because everybody knows, everybody knows everything in small towns in Georgia.

Everybody knows everything.

Gates: In small towns, period.

Linney: Yeah.

Gates: What do you think it would have been like for the kids?

Linney: Oh, I can't imagine.

Gates: I wonder if they knew.

Linney: I wonder if they even knew.

Gates: Yeah.

Linney: They had to know something.

Gates: They didn't go to a funeral.

So she has to say, "You gotta keep this secret."

Linney: Something happened.

Yeah.

Gates: Yeah.

"If anybody asks you you say your daddy is dead."

That's a heavy thing to have to live with.

Linney: Jeez...unbelievable.

Gates: We don't know what exactly transpired between Ruth and Milton, but we weren't finished with our stories of hardship in Laura's family tree.

Following the paper trail back, we came to her third great-grandmother, Jerusha Busbee, whose husband William died fighting for the confederacy.

Laura wasn't surprised to learn that she has confederates and even two documented slave owners within her southern roots.

But she never heard of Jerusha or William, or considered what they experienced.

We showed her a pension application, filed by Jerusha, which details her husband's death.

Linney: "The application of the undersigned respectfully shows that she is the widow of William Busbee, oh... Who was a bona fide soldier in the service of the confederate state and while in such letter lost his life at Fredericksburg."

Oh.

Gates: Yeah.

Linney: By a musket ball through the bowels.

Oh.

Ooh.

Signed, Jerusha Busbee.

Mm.

Yeah.

No.

You wouldn't survive that, would you?

Well... Gates: He was 35 years old when he died, leaving behind your third great grandmother, Jerusha and she had to care for your great-great-grandfather Gabriel along with four other young children.

Linney: Seems to be a theme.

Gates: You have a leitmotif going in your family tree.

Linney: Yeah.

Gates: So, when you watched your mom, struggling to raise you she was playing out a narrative line, she was like the third iteration generationally.

Linney: Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah.

That's deep in her bones.

Gates: Yeah.

Jerusha was roughly 39 years old when her husband died.

She not only had to raise her children alone, she had to run the family farm.

It was a daunting challenge, but Jerusha was up to it.

Her land remains in Laura's family today, owned by distant cousins.

Who preserved Jerusha's memory, and her image.

You ever see that?

Linney: No.

Who is that?

Gates: Laura, you're looking at the photograph of your third great-grandmother.

That is Jerusha Busbee.

Linney: That's Jerusha.

Gates: And that is from the year 1890.

Linney: Wow.

My God.

Huh.

Wow.

Gates: She's about 67 years old.

Linney: She looks a lot older than that, doesn't she?

Gates: What's it like to see a photograph of your... Linney: That's unbelievable.

Wow.

That is not a face that's had an easy time.

Gates: No.

Life hasn't been fair to women on your mom's side.

Linney: Yeah.

They've had a hard time.

Gates: They've had a hard time.

Linney: Yeah.

Gates: But on the other hand, you're sitting here.

Linney: Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

Thank you.

Amazing.

Gates: My third guest, Chloe Sevigny, came to me wondering about her paternal roots.

Her surname has a decidedly French sound to it, and she'd heard that her father's ancestors were French-Canadian.

But she didn't know anything about them.

Indeed, Chloe barely knew her father's father, a man named Harold Sevigny, who died when she was a child.

What was he like?

Sevigny: I don't have like the strongest memories of him or his wife, Ernestine.

You know, I was so young when we were spending time with them.

They moved down to Miami, so we would only see them a couple times a year and I remember they had separate beds in the bedroom.

Gates: Ooh.

Sevigny: My mom and dad were so close.

There was a lot of...they were very free with us.

I would always go in their bedroom and be like this is so bizarre.

Gates: Harold may have seemed a bit conventional to his grand-daughter.

But he was about to lead us into one of the most unusual stories we've ever uncovered.

It began in the national archives, with a naturalization record for Harold's grandfather, a Canadian named Charles Sevigny, who came to America in the 1860s, and decided to remain.

Sevigny: "I, Charles Sevigny, do solemnly swear that I will support the constitution of the United States of America, so help me God..." Gates: Have you ever heard that name before?

Charles Sevigny?

Sevigny: No.

Gates: Well, you just met your great-great-grandfather.

Sevigny: Amazing.

Wild.

Gates: And that piece of paper marks the moment the Sevignys officially became citizens in the United States.

You can even see his signature.

Sevigny: Wild.

Gates: That's when you became an American on your line.

How does it feel to see that?

Sevigny: It's pretty moving.

Gates: Do you have any idea how deeply your Canadian roots run?

Sevigny: I mean I assume they're pretty deep.

I have a friend who was in Quebec recently and she's like everybody's named Sevigny here.

She's like you've got to be related to half the people up here, Chloe.

I don't know.

Gates: Do you think that's why Charles left?

Sevigny: Too many of us up here.

Gates: Chloe's family has, in fact, been living in and around Quebec for a very long time.

We were able to trace them back to her eighth great-grandparents: Michel Rognon and Marguerite Lamain.

They were married in Quebec City in the year 1670, when Quebec was still part of Colonial France, and one detail in their marriage contract immediately caught our eye.

When this contract was drawn up, Michel would have been around 31 years old, Marguerite about 14.

Sevigny: What?

Poor Marguerite.

From child to bride.

Gates: Child and bride.

Sevigny: Yeah.

Gates: Significant age gaps between husband and wife weren't uncommon at this time, but we wanted to see if there was a story here.

I mean why do you think she was with this older man?

Sevigny: Maybe she worked for him.

Gates: Could be.

Sevigny: Or she had a sibling that was married to him that passed or... Gates: Wow.

You got good speculation.

Let's see what we found.

Please turn the page... But they were great answers.

Sevigny: I read a lot of movie scripts.

Gates: The answer to our question proved to be far more dramatic than most movie scripts.

In 1670, when Marguerite married, the population of French Colonial Canada was overwhelmingly male.

Indeed, there were roughly six male settlers for every woman.

So the King of France began offering financial incentives, in the form of dowries, to any French women who were willing to travel to Canada, and marry.

Those who accepted became known as the "filles du roi", or "daughters of the King".

And Chloe's ancestor was one of them!

Your ancestor received a dowry from Louis XIV, the King of France.

Sevigny: Wild.

Gates: So, you were in France and they were trying to encourage women to go to Canada.

So, they go I'll give you a dowry if you get on that boat and sail over there.

Sevigny: Wild.

Gates: So, what do you think Marguerite's life was like back in France before she migrated?

Sevigny: Probably pretty tough.

Yeah, yeah.

This was probably a good opportunity for her so she took it, right.

Gates: If you're a rich girl in court you're not signing up to sail across the ocean... Sevigny: No.

'Course not.

No.

Gates: Where you could die... Sevigny: Yup.

Gates: Then get to Canada where you could die or freeze to death.

For Marguerite it was a chance for a better life, clearly, and which suggests that her life in France must have been pretty harsh.

Sevigny: Insane.

Gates: The fils du roi were mostly young girls from poor families, and records suggest that Marguerite was no exception.

Her marriage contract indicates that she couldn't write or even sign her own name.

Meaning she likely had no formal education.

Canada may well have seemed to offer an opportunity.

But even so, Marguerite was taking an enormous chance, leaving behind, her family and all that she knew forever.

Gates: Can you picture yourself at 14 taking a risk like that?

Sevigny: No.

Gates: You were wild and crazy.

You hesitated because sure you could.

Sevigny: Yeah, yeah maybe I could!

Gates: I could do that.

Volkswagen bus and go to Canada.

Well, there was one significant upside to Marguerite's decision.

At the time, young girls in France were often either forced into marrying a man that their parents picked or forced to be a nun because of course it was expensive to clothe and feed a child so people wanted them out of the house as soon as possible and becoming a fille du roi meant that Marguerite could pick her own husband from among the male settlers in Canada.

So it wasn't like... Somebody bought her.

Sevigny: It wasn't like an arranged marriage.

Gates: Yeah.

She got there, she looked around, she goes that one.

Sevigny: That makes me feel better.

Poor Marguerite.

Oh, so many years ago.

Gates: Upon arriving in Quebec, the filles de roi were usually taken to a dormitory by a chaperone, where available bachelors came to court them.

Within weeks of her arrival, Marguerite would be married to Michel Rognon, a soldier turned settler.

We don't know how Marguerite met her husband but it's likely that your eighth great-grandfather, Michel, traveled to that dormitory to find a wife and then to sweet talk her or however the process worked.

But based on what we know about other women who did this I can tell you a little bit about what their meeting might have been like.

Michel had to report how he made his living and the value of his property.

Marguerite was allowed to ask him questions about his home and finances.

Can you imagine being a 14-year-old girl asking a man that you might marry questions like that?

Sevigny: No.

But I do always say I'm from hearty New England stock so there's my proof.

Gates: You're from hearty Canadian stock!

Sevigny: Yeah.

Gates: Marguerite would prove to be the very definition of hearty stock.

She adapted to the Canadian winters, and frontier life.

And she endured tragedy.

In 1684, when she was roughly 28 years old, Michel died, leaving her alone with six children under the age of eleven.

How do you think your eighth great-grandmother Marguerite coped suddenly becoming a single mother to six children?

Sevigny: Poor girl.

I don't know.

That must have been rough.

She'd have to get married again.

Gates: Two months to the day.

Bye, Michel.

Two months to the day after Michel died, Marguerite married a man named Pierre Mercier.

Sevigny: Good for him for taking her on with all those children.

Gates: Well, Marguerite and Pierre had eight more children together.

Sevigny: Wild.

Gates: What does it mean to you to have come from a woman like Marguerite?

It's pretty amazing.

Sevigny: Yeah.

I mean it makes me feel proud and, you know, and I'm in awe you know that women sacrificed in that way and it's an incredible contribution, obviously.

You know.

It's touching.

Gates: Marguerite lived to be roughly 57 years old, at a time when the average life expectancy of a Canadian woman was less than 45!

But Marguerite did more than simply survive.

She and her fellow fille du roi are celebrated, even today, because they left behind a tremendous legacy: children, who would populate French Canada.

Marguerite had 14 children by two different husbands and according to one study, by December 31, 1729, 94 residents of Quebec were Marguerite's descendants.

Because your children have children.

Sevigny: What?

Yes, wow.

So, no wonder they're held in such high regard.

Gates: Yeah.

Exactly.

But all these people are related to you.

You have a bazillion cousins in Canada.

Sevigny: Just like my friend said.

Gates: Guess what, they all want loans.

Sevigny: Get in line.

Gates: That's funny.

We had already introduced Michael Moore to Quaker ancestors on his father's family tree.

Now, turning to his maternal roots, Michael expected us to go to Ireland, in search of ancestors whom, he believed, came to the United States in the 1840s, fleeing the infamous potato famine.

But Michael was in for a surprise.

While many of his maternal lines did trace to Ireland, we found one that did not.

It led to Michael's eighth great-grandfather, a man named John Wattles, who was already living in Colonial Massachusetts in the 1650s!

Have you ever heard of John Wattles, your eighth great-grandfather?

Moore: No.

I have not heard of John Wattles, and, um, I'm just kind of soaking up the moment here looking at this name because I'm thinking I'm here because the Irish were being starved.

And ran out of potatoes so the British wouldn't feed us, so I'm thinking that we're all...we came in the 1800s.

Gates: But no, you came a long time before that.

Moore: We're talking almost 400 years.

Gates: 17, 18, 19, 20... Almost 400 years... 400 years of your family's history on American soil.

Moore: Of being here.

Right.

Don't I win a prize or something for this?

This...what's... Gates: It's a big deal.

Moore: Who comes out from behind the curtain right now and presents me with a new car?

Gates: George Washington?

Moore: George... Gates: We don't give out prizes, but if we did, Michael might win one, not for the year his ancestor came to this country, but for the way he came.

The story begins with the manifest of a ship called "The John and Sarah", which sailed from London to Boston in November of 1651.

Moore: Wow.

Gates: You're looking at the record of the ship that brought your ancestor to America.

That is the moment that ancestor arrived.

Moore: So we're only... We're 30 years after the Mayflower.

That's all this is.

Gates: Yeah.

Moore: Right?

Gates: 31 years.

Moore: 31 years.

Gates: And what's more, this ship, "The John and Sarah" Moore: Right.

Gates: Wasn't just any ship.

It had unique cargo.

Your ancestor arrived in Boston along with nearly 300 other men and they all had one thing in common, and I want you to guess what that was.

Moore: Um, 300 men and they all had something in common and it's the 1650s and they're coming from England.

Um, bad teeth?

Gates: I'm sure they had bad teeth.

Moore: I don't...I have...I would have no idea what is going on here.

Gates: Please turn the page.

This is a letter from the year 1651, the year your ancestor arrived in Boston.

Moore: Oh my God.

Gates: It was written by a Massachusetts reverend named John Cotton, who was quite famous.

Would you be kind enough to read the highlighted passage?

Moore: Wow.

"The Scots have not been sold for slaves to perpetual servitude, but for six or seven or eight years."

Gates: This is the first time that we've seen a white person described as a slave.

In fact, we checked it.

We thought it must be a mistake that they must be indentured servants.

But the word is "slave."

Moore: What is going on?

Gates: Did you ever think you'd possibly could've been descended from a slave?

Moore: Uh, no.

Who were these people?

I mean seriously.

Gates: The answer to Michael's question lay in one word from John Cotton's letter: "Scots."

The men on the ship were Scottish.

And they were being held, as slaves, because they had made a very unfortunate decision back in their homeland.

In 1649, at the height of the English civil war, Oliver Cromwell overthrew King Charles I of England.

Cromwell was, ostensibly, a reformer, attempting to bring England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales under parliamentary control.

But the Scottish didn't see him that way.

Hoping to restore the monarchy, they raised an army, invaded England, and were crushed in battle.

Michael's ancestor, John Wattles, served in that royalist army, and shared the fate of many of its soldiers.

Roughly 10,000 royalists were captured, including your eighth great-grandfather, John.

Moore: Wow.

That is amazing.

Gates: He was a prisoner of war.

Moore: And I've never heard of any Scottish um... Gates: Yeah, Mr.

Irishman, did you know you had any Scottish an...ancestry?

Moore: No, and...and...and... And that's a good thing.

I mean if you've ever met anybody from Scotland they're an appropriately angry people so.

Gates: Well, um, John Wattles, your eighth great-grandfather was Scottish.

That's the first surprise.

He was brought to Massachusetts by the English and sold as a laborer.

Moore: Wow.

Gates: And it was a pivotal moment in your family's life, Michael, because your eighth great-grandfather never saw Scotland again.

Moore: Right, because he was captured, he was a POW.

Gates: He was forced to march over 100 miles to London with scarce provisions only to be sold into slavery to Massachusetts as a prisoner of war.

Moore: Wow.

Wow.

That's an amazing story.

Gates: John Wattles' "amazing story" wasn't over yet.

There was a final twist still to come.

After spending roughly seven years in forced labor, John became a free man and settled in Chelmsford, a town outside of Boston.

It would prove to be yet another unfortunate decision.

Moore: "Four years later Indian troubles throughout the New England colony culminated in an open conflict known as "King Philip's War".

Chelmsford was attacked in February, March and April of 1676.

Homes were burned and people were tortured and slain.

John Wattles was numbered among the fallen."

Gates: Your eighth great-grandfather was killed by Native Americans.

Moore: Well, you know, it was the Indians' land and they were being killed and uh, diseased and the whole thing, so.

I mean, I'm...I'm sorry, you know, it's a...it's a past relative, whatever, but um, you know, I would say to any white person who came here back then, what made you think that you could come here and take other people's land and kill them and have a policy that treated them as...as if they were less than human and um, here's the culmination of that.

Gates: We had already taken Laura Linney back to the 1860s on her mother's family tree, introducing her to generation after generation of women who had struggled to keep their families together.

Now, turning to her father's ancestry, we encountered the opposite: A long line of men who had seen a great deal of stability, including not only her celebrated playwright father, but also a United States congressman and a state senator, stretching back in an unbroken line to Colonial Virginia.

So let's begin with you at the bottom, then you can see your dad.

Linney: Right.

Gates: Keep going up.

Linney: RZ III, II, I, William C. Gates: William C. is your third great grandfather.

Linney: Then there's Zachariah.

Gates: And his father, who is your fifth great grandfather.

Linney: Holy mackerel.

Gates: Your great-great-great -great-great-grandfather.

Linney: Wow.

Wow.

Gates: Was named William Linney, and William Linney was born October 7, 1739, Laura.

Linney: Good lord.

Gates: Deep roots.

Linney: Yeah.

I'm American.

I'm American.

Gates: William Linney, Laura's 5th great grandfather, is the oldest Linney ancestor we could identify on her direct paternal line.

But that isn't the only thing that makes William special.

Linney: "Mr.

Linney served as an apprentice seven years, the blacksmith trade.

He then came to America and landed from the Neptune on the coast of Virginia February 27, 1768."

Wow.

Wow.

So it started with him?

Gates: Yes.

He was your original immigrant ancestor on this line of your family tree.

Linney: Wow.

Wow.

Gates: Your fifth great grandfather.

And you had no idea?

Linney: No.

Gates: You didn't know where they came from.

You presumed England?

Linney: I, I presumed England.

I had heard Wales, I'd heard, you know, but in my family you never know what's, you know, a theatrical tale and what is, you know, what's a fact.

Look at that.

Gates: As it turns out, William Linney's story might well have been invented by Laura's theatrical father.

Records show that William was, in fact, born in England.

And that he didn't exactly leave his homeland under the best of circumstances.

Get ready for this.

That is a passenger list from the ship on which your ancestor sailed from 1768.

Linney: Holy mackerel.

"Felons transported from London to Virginia by the Neptune in January 1768."

Gates: He is banished from England.

He is being sent into exile.

Now we all know about Australia and convicts, but did you know that convicts were sent to the American colonies?

Linney: No.

United states.

No.

Gates: Transportation of convicts to the American colonies in the 18th century was a way for England to rid the country of criminals without killing them.

Linney: Wow.

Gates: Want to guess what... Linney: I want to know.

What did he do?

Gates: William did?

Linney: What did he do?

What did he do?

Gates: Would you please turn the page.

This is a transcript of his trial from 1767.

Linney: "Thomas Dollymore was indicted for stealing and William Linney for receiving 54 iron hoops for pails, one truss-hoop, and one riveting tool, part of the said goods.

Well knowing them to have been stolen.

The justice said, "Mr.

Linney, you hear what the lad has said.

Have you anything to say?"

Linney said, "No.

I own I had the goods."

Gates: I own I had the goods.

Linney: So he fessed up.

Gates: William's trial transcript indicates that he confessed to receiving and then selling stolen property.

For his punishment, he was not only banned from England for 14 years, but he was required to foot the bill for his passage!

It's not exactly surprising that William never returned to England, and fascinating to think that such a distinguished family grew from such humble origins.

Linney: Wow.

That's unbelievable.

Gates: It's unbelievable.

William Linney, for a guy who sold purloined goods had a pretty good line of descendants.

Linney: Yes.

Yeah.

I guess I have that judge to thank for that.

Wow.

Amazing.

Gates: What's it like to see that?

Linney: It's...it's it's fantastic and it's appropriately juicy for my family.

So, it's, you know, it fits in well.

Gates: We were nearing the end of the journey for my three guests.

The paper trail had run out, it was time to show them their family trees, now filled with people whose names they'd never heard before.

Sevigny: Holy Toledo.

Wow!

Gates: For all three, it was a moment of awe.

Moore: This is amazing.

Linney: Wow!

Gates: These are all the ancestors that we found.

A chance to see how their own lives fit into a chain first forged a long time ago.

Linney: It just goes to show that, you know, you think you're this autonomous sort of thing and then you realize you have all these people to thank.

Gates: Oh, that's beautiful.

Linney: You know, you have all of these people to thank and all of these people who mean something to you and you would mean something to them, you know, it's amazing, it's amazing, family.

Gates: Family.

This is your family.

Linney: Yeah, family.

Moore: My soul has been touched by this because...because who I am and...and how I feel and what I believe in um, just didn't appear and it... It came through a shared experience by many, many people passed down and it's a weird moment, it's like I'm getting a second birthday here... Gates: Yes.

Moore: Because...you've told me something about my formation, my birth essentially as a human, as an American... Gates: It's revelation of why you are who you are.

Moore: Yes.

Sevigny: I mean I'm dumbfounded.

Gates: You know, you're part of Canadian history, I mean big time.

Sevigny: Big time.

Yeah.

I mean I feel like I would like to go up there and go around and do some research, I mean this has given me a window and an incentive to try and find out more about these people that came over and sacrificed and I mean, what a rich history.

Gates: That's the end of our search for the ancestors of Laura Linney, Michael Moore, and Chloe Sevigny.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots".

Narrator: Next time on "Finding Your Roots" Sanders: Oh my God... Narrator: We turn back the clock to revisit compelling stories from last season.

Armisen: Why hasn't anyone told me this?

Duvernay: Incredible!

Narrator: Favorite episodes you may have missed.

David: Now that's something.

Narrator: Then, join us Tuesday April 2nd, when new episodes and new guests return.

Abramovic: This is like new for me totally.

Burrell: That is incredible.

Gates: You ready to find out?

Madison: All this time I've been waiting.

Narrator: Join us next time on "Finding Your Roots".

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S5 Ep8 | 30s | Dr. Gates explores the stories of Laura Linney, Michael Moore and Chloë Sevigny. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: