AHA! | 633

Season 6 Episode 33 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Colorful public art, Roman art, and a performance.

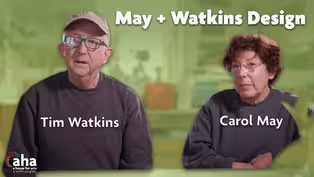

Check out the colorful public art installations and interactive exhibits of Carol May and Tim Watkins. How much do we actually know about the roots of the value of Roman art? Associate Professor Elizabeth Marlowe explains. Michael Eck performs "One of the Old Songs" and more.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

AHA! A House for Arts is a local public television program presented by WMHT

Support provided by M&T Bank, the Leo Cox Beach Philanthropic Foundation, and is also provided by contributors to the WMHT Venture Fund including Chet and Karen Opalka, Robert & Doris...

AHA! | 633

Season 6 Episode 33 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Check out the colorful public art installations and interactive exhibits of Carol May and Tim Watkins. How much do we actually know about the roots of the value of Roman art? Associate Professor Elizabeth Marlowe explains. Michael Eck performs "One of the Old Songs" and more.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch AHA! A House for Arts

AHA! A House for Arts is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(upbeat music) - [Lara] Discover the playful synergy of May & Watkins Design's sculptures.

Colgate University Professor Elizabeth Marlowe gives us a fresh take on an Ancient Roman art, and catch a performance by Michael Eck.

It's all ahead on this episode of AHA, A House for Arts.

- [Male Narrator] Funding for AHA has been provided by your contribution, and by contributions to the WMHT Venture Fund.

Contributors include Chet and Karen Opalka, Robert and Doris Fischer Malesardi, the Alexander and Marjorie Hover Foundation, and the Robison Family Foundation.

- At M&T Bank, we understand that the vitality of our communities is crucial to our continued success.

That's why we take an active role in our community.

M&T Bank is pleased to support WMHT programming that highlights the arts, and we invite you to do the same.

(jazzy music) - Hi, I'm Lara Ayad, and this is AHA, A House for Arts, a place for all things creative.

Let's send it right over to Matt Rogowicz for today's field segment.

- I'm here in Athens, New York to get a behind the scenes look at the beautiful public art of May & Watkins Design.

Let's go.

- May & Watkins Design is, it's an art company.

We create art.

We conceive it, we design it, we build it, we install it.

It's done for mostly public art, lots of parks, but also sometimes private commissions for larger institutions.

Tim was working at the Children's Museum of Manhattan and he and a group of people were loosely putting together a show, and he brought me in to paint the murals, which that's how I started, I was painting murals for these exhibits.

And then he left and decided to do a show in St. Louis?

- St. Louis, yeah.

- And I was suddenly left with designing this thing, putting this thing together and running it, which I did.

It was very successful.

I believe it was picked up by the New York Times, was it?

- I think it was, yeah.

- And the host committee for the Grammys saw it and they hired us to do a commission for them.

And they gave us $40,000 and said here, we want this particular - [Tim] Which in those days was a lot more than it is now.

- These particular venues do a creative exhibit.

We did, and at the time I thought to myself Hmm, people are paying us to do this and they're asking us to do this, maybe this is what we should do.

So we, we started the company really very informally what did we know about business?

But the moment we started it, it kind of took off.

When we approach a project, we're usually given a site and we listen to the parameters of what the clients are trying to achieve, and usually they're very broad.

And then we try to create a unique piece that that satisfies us and satisfies them.

So some of our pieces will be in concrete, some of them will be in mosaic, some will be in steel, some will be in foam, some will be painted.

It depends on where we are in the time and what we think best suits the vision.

- So we're always looking for new things to introduce to the work, but there is a foundation of form that I think it's fairly obvious in the work.

- [Carol] Yeah, it's not geometric, it's not minimal.

- Yeah.

- [Carol] Yeah.

Well, the process actually starts with Tim.

He starts by - [Tim] Oh, I call it chumming the waters.

There are, you know, there are Listservs out there for public art and, you know, we apply to those.

So that's where we start.

- [Carol] Well, we don't.

You do that.

- Okay.

Well, we are "we," - Yeah.

- We get into a finalists stage fairly often, you know.

- [Carol] And usually that means there are three or four artists selected to produce concepts and do a presentation, and you're paid a small stipend.

And that's where I come in with coming up with a visual and an idea for it, and we always work together on that.

We're very engaged in whatever project we're really doing right now, and we think, Oh, this is new, this is what we really want to do right now.

I mean, what we're doing right now, the project that's going on right downstairs, it's for Aurora, Colorado.

We're very excited about it because we're using a different way of using rolling steel, large planes of it instead of a simpler, lighter way of fabricating.

And it has a very organic, gutsy look that we haven't achieved in metal yet.

- [Crew Person] Is this it?

- That's it.

- [Crew Person] Can we?

- Yeah, you can just lift it up.

Just, it's really don't It's not fragile.

These things get thrown around, believe me.

This was the initial concept model and you can see how rough it is.

And then this was actually the model that won the commission.

- This is for a park, and so they wanted something that offered a substantial piece of sculpture and seating.

- [Carol] This was done quickly, there are entrapment areas, there could be hazardous areas, you have to really look at that, and - We don't want to impale anybody on, on the leaves.

- I work in the shop, we take the models and the drawings that Tim and Carol put together and we make them full-size.

We scale them up from a model size and create the work.

- Right now we have two people working with us, and one of them, John Franzen, who is actually he's from Athens, he was sitting across the street 14 years ago not doing anything, so we put him to work and he's actually, you know, he's turned into an amazing fabricator, he really has.

- I was literally arranging some rocks for a bed in front of my house next door, and Carol walked by and said, "Oh, you're an artist."

I said, "well, no, I just put..." "How'd you learn how to do that?"

"Well, just kind of make them look nice."

"Do you know how use a grinder?"

My father always told me say yes to everything.

So I said, yeah, yeah.

And two years later here I am using the grinder, so.

- We're a little bit crazy in the sense of being so immersed in this and they have that same, they have that same quality.

I think probably all four of us are a little hard to live with, but we get along really well because they will work on something until it's perfect.

- Carol is, she's much more of a perfectionist than I am.

- We fight all the time and I'm always mad at him.

- [Crew Person] The truth.

- No, seriously.

It's, he's daring, and he also brings a reality to the work that I can sometimes lose.

- Most of the pieces stand up to time, at least as far as I'm concerned, you know, it's some pieces, I'll say, God, we should've done that or, you know, what were we thinking?

But most of them do stand up and, you know, that makes me feel good.

I mean, these basically if I can say it, these are our babies, you know.

And we're putting them out there and, you know, we're getting to see, and watching people react with them is always really exciting.

- [Carol] And love them sometimes, which is nice.

- Yeah.

- Elizabeth Marlowe is an Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Colgate University.

Her research focuses on Ancient Roman art and its value.

From the museum to the black market, how much do we actually know about the roots of this classic subject?

Let's chat with Elizabeth to find out.

Liz, welcome to A House for Arts, it's such a pleasure having you on the show.

- Thank you so much for having me.

I'm really excited to be here, it's the first time I've left the house in a year.

- It's the first time we've been to many spaces, right?

In a long time.

- Yeah.

- Well, you know, Liz, I know you've played many different roles as a columnist online, as a professor, a scholar, and as a curator too.

And I understand you also teach a seminar at Colgate University called Looting, Faking and Understanding Antiquities, right?

Which sounds amazing, I want to sign up for this class.

So I know it's about Ancient Roman art, and we talk about Ancient Rome all the time in books and movies, and you see Ancient Roman art in museums, but what I understand, and tell us more about this, is your classes and your publications expose the kind of, the dark underbelly of this classic subject.

- Yeah.

- Yeah.

Tell us more about that.

- Yeah.

The dark underbelly, I like that idea.

I mean, what I'm trying to teach both my students and also to communicate in my writings is this idea that Classical art doesn't come to us in a kind of pure state.

When we see these beautiful marble statues in museums there's always stories behind how that object got here, why that object is in such pristine condition.

There's always information that labels aren't telling us, stories that aren't being told.

So I am trying to encourage my readers and my students to read between the lines and to think critically about what stories aren't being told in those kinds of settings.

- So, this is fascinating, Liz.

What's an example of a story that hasn't been told that you think kind of is a little messier than maybe museums or books have typically shown us.

- Yeah, there's an example, there's a piece I'm writing right now that focuses on a statue at the Metropolitan Museum that - [Lara] The Metropolitan Museum in New York.

- [Elizabeth] In New York City, yes.

When this statue was published, in the eighties and nineties when it first surfaced, publications stated very explicitly that this came from a particular site in Turkey, a site called Bubon, which was a place where there was a cult dedicated to the Roman emperors.

So statues of emperors were set up as gods in this building.

And there's about 20 of these life-size bronze statues of emperors represented as gods that were all found at this site.

- [Lara] Right, and the one at the MET is one of those 20.

- And the one at the MET is one of them.

They were all smuggled out of the country.

They started showing up in American museums and collections.

And when they were first surfacing in the eighties and nineties, these publications openly said that that's where they came from.

- [Lara] Like that's where they were originally made and meant to be displayed.

- Yes, that was where they were, they were made for that setting, they were displayed in that setting, they ended up being buried in that setting and then rediscovered in that setting, all - [Lara] Right, and that's been the narrative for many years.

- [Elizabeth] That was always the way these were understood until public attitudes about looting and smuggling and cultural property started to shift.

So now, if you look at the label at the Metropolitan Museum it says none of that.

There's no mention of this site in Turkey.

There's no mention of the Imperial cult.

There's no mention of how those objects got out.

And in fact, the label goes on and on and on about how we don't know what this is.

It could be an emperor, it could be a god, it could be Greek, it could be Roman.

So the museum is like actively pretending not to know the real story behind this object.

- [Lara] So, I have two questions then for you, Liz, first of all, and maybe we can come back to this, why are museums acting like the histories of these objects are so neat and tidy and sterile?

And then two, how, what did you discover in your research?

Like, what exactly is it that people should know about these kinds of objects and these statues?

- Yeah, those are, those are good questions.

So museums are telling these stories in ways that protect their authority.

So their right to continue to own these objects, and to have full say over their disposition, what the label says, how they are displayed, and certainly to kind of preemptively fend off any repatriation claim from the countries that they were stolen from.

- [Lara] So it's almost as if the museum label, if it negates all this information, it creates a blank slate for the museum to then jump in and be like, well, actually this is our property, we own this.

- Yes, that's exactly right.

That's exactly right.

Yeah.

It's a kind of preemptive staving off of a repatriation claim.

So museums routinely hide information that they have about where looted objects come from so that they will not attract the attention of the source country.

So anytime you see vague labels like East Greek or like North Africa, you know Western - [Lara] Which is like the size of the continental United States, like what does that mean?

- [Elizabeth] Right, Western Roman Empire, right?

There's all these terms that are euphemisms that usually mean we know more than we are saying here, but museums never want to most museums don't want to acknowledge that because the attitude is so much all about the retention of their possessions.

- I want to come back to the way that museums sort of position their own authority and flesh that out a bit in current debates we've had, but it's making me think 'cause I was doing some research online and looking at antiquities looting.

I know a little bit about it only because of my own background.

I understand that the looting of antiquities has been a problem for at least a decade, but it's gotten worse over the course of the pandemic lockdown.

So for instance, a lot of heritage sites in in Iraq where their Mesopotamian heritage sites have been being looted even more over the past year because there's no one overseeing these sites.

Why is the looting of antiquities so widespread and so pervasive?

- It's a great question.

And it goes back way more than a decade.

I mean, it was sort of always happening.

One of the big milestones was when Getty showed up on the scene with his hundreds of millions of dollars to spend on acquisitions for the new museum, right.

Suddenly a supply needed to be generated.

- [Lara] This is the founder of the Getty Collection.

- Right, the founder of the Getty, exactly.

- Are museums now at least starting to address this very kind of gritty, unattractive history of antiquities circulation and the movement of these objects in countries and across the world, because I'm hearing a lot about, say, we've been hearing in the news about how museums are closed because of the pandemic, but there's also these conversations going on in some circles about quote unquote "decolonizing the museum."

Can you tell us a little more about what that means?

I mean, I know there's been calls to like, for the British Museum in London to repatriate or give back these early bronzes from the kingdom of Benin in West Africa and to send them back to what's now Nigeria, can you tell us a bit though about like, is that what decolonizing looks like or is there more to it than that?

- Yeah, that's a great question.

So, so decolonizing, I think sort of in its truest sense is really focusing on the legacies of colonialism.

So, most of the British Museum can be understood as like a giant legacy of colonialism.

The antiquities that I am looking at, some of them were extracted under colonial circumstances.

So when, you know, European aristocrats could just go help themselves, you know, could go to the desert and start digging as the Ottoman Empire is declining, for example.

- [Lara] In parts of Turkey and parts of the Mediterranean.

- [Elizabeth] Exactly.

But a lot of the objects that are coming onto the market today were pried loose from their sites of origin not by the forces of colonialism, but by local, impoverished, rural landowners, farmers, workers, peasants, who know that there is this market in the West.

So they are doing their own digging, right?

It's less the case nowadays that foreigners are showing up and doing the actual extraction.

Rather, what happens now is that it's the local populations who have networks to middlemen, to smugglers who get them out to Switzerland.

- It sounds like the transparency about those messy histories is really the key to kind of repairing that and really changing the role of museums in that way.

- [Elizabeth] I think so.

I think so.

You know, there are those who would argue that what we always need to be focusing on is returning these objects, and I think in cases where there are source communities from where these objects came that still worship these objects, that are living descendants of the people for whom these were created, then I think we should be returning them as well.

Where it gets messier is what do we do with the hundreds of thousands of objects that belong to the Ancient Romans, for example, right?

Who's to say who the living descendant communities are in that case?

- [Lara] Right, is it the modern Italians?

Is it - Right.

Right.

So in those cases, I think what really matters is this kind of radical transparency that we're starting to see in more and more museums.

But I think it requires museums to take some steps that they historically just have not been willing to take, to admit that they often got these objects through dirty means, and that their knowledge is not total, right, they are not omniscient.

Even the smartest, - [Lara] It's not the be all, end all, - [Elizabeth] Right, even the smartest, most educated, qualified curator can't really look at an object and tell you "I know exactly what this is" in the way that they could if they were looking at an object that had a known archeological context, right?

The difference in those two kinds of knowledges, I think needs to be much more openly acknowledged.

- [Lara] Yeah.

Liz, it was such a pleasure having you on the show.

It's so great talking about this, and I can't wait to maybe sit in on one of your classes or read one of your books.

- That would be great, it would be a pleasure to have you.

- All right, thanks a lot.

- Thank you.

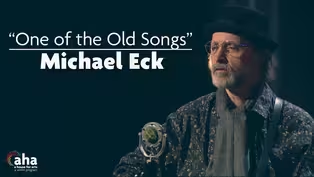

- Please welcome Michael Eck.

- Here's brand new one.

It's a song called Paint Me Blue.

(guitar strumming) If you wanna paint me, paint me blue.

You packed up your brushes, pinned back your long blonde hair.

Stashed the oils in the sienna box, tiptoed down the garden stairs.

You had the motor running, in French he spoke your name.

He was handsome, you were beautiful, who was I to blame?

Blue as the sky above, blue as the sea below, blue as the ice in your eye, when you turn to go.

If you wanna paint me, paint me blue.

Cerulean was hope you said, turquoise the color of tears.

A stray canvas in the bedroom has been hanging blank for years.

You took one last good look that day and framed the scene in your mind.

A woman signing in the foreground, a portrait of a man left behind.

Blue as the sky above, blue as the sea below, blue as the ice in your eye when you turned to go.

If you wanna paint me, paint me blue.

Blue as the sky above, blue as the sea below, blue as the ice in your eye when you turned to go.

If you wanna paint me, paint me blue.

Here's one called One of the Old Songs.

(guitar strumming) Let's sing one of the old songs.

Melody from days long ago.

Let's sing one of the old songs, pick out one we all know.

Too many friends gone before us, too many tales of woe.

Let's sing one of the old songs, before it's our own time to go.

We're gathered with friends and with family, spinning yarns to let up the night.

There's drink, and there's talk, and there's music, and everyone's feeling all right.

And as the clock, it ticks ever quicker, as the evening grows to its close, we remember just why we're laughing, it's to fight the darkness so close.

Let's sing one of the old songs, a melody from days long ago.

Let's sing one of the old songs, pick out one we all know.

Too many friends gone before us, too many tales of woe, let's sing one of the old songs before it's our own time to go.

There's not a song that's worth singing that doesn't carry sorrow in its tune.

There's not a life that's worth living that doesn't end too soon.

Let's sing one of the old songs, a melody from days long ago.

Let's sing one of the old songs, pick out one we all know.

Too many friends gone before us, too many tales of woe.

Let's sing one of the old songs before it's our own time to go.

Too many friends gone before us, too many tales of woe.

Let's sing one of the old songs before it's our own time to go.

Let's sing one of the old songs before it's our own time.

- Thanks for joining us.

For more arts visit www.wmht.org/aha and be sure to connect with WMHT on social.

I'm Lara Ayad.

Thanks for watching.

- The Grammys were slides.

We didn't have digital, we didn't have computers, did we?

- No, no, we didn't.

We were, we were starting to put things on - What year was the Grammys?

- '94?

- I was using a computer, but it was really, I was using a Mac.

- Yeah.

It had a sloppy floppy disc drive.

- [Male Narrator] Funding for AHA has been provided by your contribution and by contributions to the WMHT Venture Fund.

contributors include Chet and Karen Opalka, Robert and Doris Fischer Malesardi, the Alexander and Marjorie Hover Foundation, and the Robison family foundation.

- at M&T Bank, we understand that the vitality of our communities is crucial to our continued success.

That's why we take an active role in our community.

M&T Bank is pleased to support WMHT programming that highlights the arts, and we invite you to do the same.

AHA! 633 | Elizabeth Marlowe on Ancient Roman Art

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep33 | 10m 31s | How much do we actually know about the roots of Roman Art? (10m 31s)

AHA! 633 | May + Watkins Design

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep33 | 7m 57s | See how May + Watkins Design brings colorful creations to life. (7m 57s)

AHA! 633 | Michael Eck "One Of The Old Songs"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep33 | 2m 51s | Michael Eck performs "One Of The Old Songs" on AHA! A House for Arts at WMHT Studios. (2m 51s)

AHA! 633 | Michael Eck "Paint Me Blue"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep33 | 2m 26s | Michael Eck performs "Paint Me Blue" on AHA! A House for Arts at WMHT Studios. (2m 26s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S6 Ep33 | 30s | Colorful public art, Roman art, and a performance. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

AHA! A House for Arts is a local public television program presented by WMHT

Support provided by M&T Bank, the Leo Cox Beach Philanthropic Foundation, and is also provided by contributors to the WMHT Venture Fund including Chet and Karen Opalka, Robert & Doris...